Explore the museum

Discover Dickens through his work, his home and the things that mattered to him most

Dickens’s Legacy – Past, Present and Future

100 years on, our door remains open for all to explore the legacy of Charles Dickens – past, present and future.

Dickens in Antarctica

David Copperfield taken on Scott's Antarctic expedition in 1910

DH483 © Charles Dickens Museum

Dickens's global reach

£10 note featuring Charles Dickens

DH578 © Charles Dickens Museum

The Last Bid

Photograph of the auction of Charles Dickens's personal effects, August 1870

DH1230 © Charles Dickens Museum

Dickens in Doughty Street: 100 Years of the Charles Dickens Museum

Step into the world of Charles Dickens and the Museum’s role in preserving his legacy.

Showtime!

Delve into Dickens adaptations from 1837 to modern-day and the reasons behind their continual recreation.

The Many Adventures of Oliver Twist

Explore the many adaptations of Oliver Twist for theatre, radio, film and television.

Creating a Legacy

Dickens read and performed his own works to make money, reach new audiences and preserve his legacy.

Theatrical Dickens

Dickens acted in, wrote, produced and adapted his own and others' work for theatre.

Hope through the Smoke

Dickens’s Watercolour of The Old Curiosity Shop by George Cattermole, 1840. DH98.1.

Breathing in the Fog

Letter from Charles Dickens to Helen Dickens, 16 July 1860. A892.

Purchased with support from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund, the Friends of the National Library and the Dickens Fellowship.

Letter to Thomas Beard

Letter to Thomas Beard, 31 March 1843. A90.

Horse Attack

Letter to Lord Robertson, 6 May 1847. A933.

Purchased with support from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund, the Friends of the National Library and the Dickens Fellowship

Cornelius Felton

Dickens writes to friend, Cornelius Felton, about how in a different life he would like to have been a Theatre Manager.

The Eagle and the Raven

Letter to Edwin Landseer, 23 July 1845. A241.

'Scrooge', 1970

Programme and photographs, Scrooge, 1970

DH1252 © Charles Dickens Museum

Pets in Verse

Printed poem, ‘To Miss Dickens’ Pomeranian, Mrs Bouncer’ by Percy Fitzgerald. NN575.

Promotional Brochure for 'Scrooge', 1935

Promotional brochure for Henry Edwards' film Scrooge, 1935.

[lib] 7390 © Charles Dickens Museum

Out for a Drive

Copy of an image of Dickens and his family at Gad’s Hill Place by Robert Hindry Mason, 1860s.

A Horse Called Duke

Wooden name plate for Dickens’s horse, Duke, c. 1850s. DH1101.

Programme for Oliver!, 1968

Programme for Oliver!, 1968

[lib] 4552 © Charles Dickens Museum

Dickens and Turk

Carte de visite of Dickens and Turk by Robert Hindry Mason, c.1860s. DH707.b.

Edwin Landseer's Boxer

‘The Cricket on the Hearth’, 1858. [lib] 2630.

Feature on Oliver Twist, 1923

Feature on Oliver Twist, in 'Picture Show Art Supplement', 24 February 1923

[lib] 7391 © Charles Dickens Museum

Bull's-eye Escapes

‘Sikes attempting to destroy his dog’, ‘Oliver Twist’, 1838. [Lib] 2319.3

Reading Copy of The Story of Little Dombey

The Story of Little Dombey, reading edition, 1858

[lib] 997 © Charles Dickens Museum

Playbill for Great Expectations

Playbill for Great Expectations Lyceum Theatre, Newport, about 1926

DH802 © Charles Dickens Museum

A Scene of Domessticity

Letter to George Cruikshank, January 1838. A364.

'Used Up!' Prompt Book

Charles Dickens's acting copy of Used Up playscript

[lib] 5169 © Charles Dickens Museum

Lady Jane

‘Mr Krook and his cat’ by Harry Furniss from ‘Bleak House’, 1910. [Lib] 1044.11.

Firm Friends

Pen and ink sketch of ‘Barnaby Rudge and Grip the Raven’ by Fred Barnard, c.1885. DH384.15.

Snuff Box

Snuff box gifted by Charles Dickens to Douglas Jerrold

DH110 © Charles Dickens Museum

Grip and his family

The Children of Charles Dickens and Grip the raven by Daniel Maclise, Pencil and wash drawing, 1841. DH743.

Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi

Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi, Vol. II (First edition), 1838

[lib] 6143 © Charles Dickens Museum

Playbill for Oliver Twist, 1861

Playbill for Oliver Twist at Holliday Street Theatre, Baltimore, 1861

DH804 © Charles Dickens Museum

Image taken by Lewis Bush, 2025. This image is provided under Creative Commons License 4.0 until 1 April 2031, made possible with The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Playbill for The Cricket on the Hearth, 1846

Playbill for The Cricket on the Hearth, Theatre Royal, Lyceum, 1846

DH792 © Charles Dickens Museum

Image taken by Lewis Bush, 2025. This image is provided under Creative Commons License 4.0 until 1 April 2031, made possible with The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

'Spitalfields' by William Henry Wills

Fire Poker

A Love of Theatre

Explore more about Dickens's love of theatre.

Sketch of Dickens performing

Sketch of Dickens performing in 'Mr. Nightingale’s Diary', 1857

DH1243 © Charles Dickens Museum

The Love That Never Was

This jug was once owned by Charles Dickens, then later by Annie Thomas, the heroine of this story.

The Scandalous Sister? Georgina Hogarth

Jordan Evans-Hill speaks to Christine Skelton, the author of 'Charles Dickens and Georgina Hogarth: A Curious and Enduring Relationship.'

Bonus: Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins

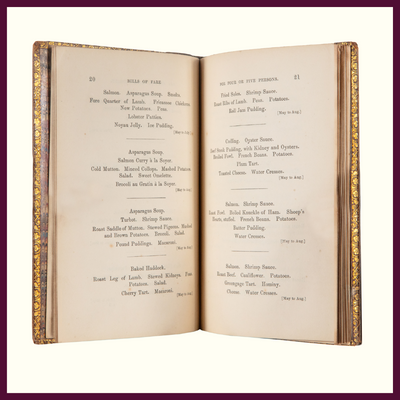

Episode Six: Food, Glorious Food

Episode Five: Striking A Blow

Episode Four: Ignorance and Want

Episode Three: Making A Christmas Carol

Episode Two: Scrooge's London

Episode One: Charles Dickens and Christmas